Yesterday I received the traditional pre-election mail that includes the propaganda from all the candidates in my constituency. With 20 candidates, this makes for a lot of dead trees. In fact, I received leaflets for 17 candidates, most of them also adding their ballot paper.

All 17 leaflets on my kitchen table

Of course, this arrived only 24 hours before the closure of internet voting, and I had already voted. I still found them very interesting, both because they represent a very wide spectrum of opinions and because they have different styles. I will present these leaflets here in no particular order (probably in fact the order in which I found them folded in the envelope). Because there are so many, the introduction to those who want to be my MP will take place in several instalments.

1. Denys Dhiver, Parti chrétien démocrate et France Ecologie. Slogan: ‘La droite de convictions’ (a Right with convictions?). This is a party founded Christine Boutin, a traditional Catholic politician, former Housing minister of Sarkozy and candidate in the 2002 presidential election. Lives in England (nothing more specific).

What are these convictions?, you might wonder. The first one is defending family (that is, a man and a woman) and life (‘from conception’, meaning that he’s against abortion), restoring authority in schools, defending agriculture and SMEs, fighting against rural population exodus, changing the tax regime by including creating a universal basic income and taxing all revenues, creating a compulsory national service to teach young people community service and respect for authority (in case school failed, I guess), changing the presidential term to a non-renewable 7-year term and decreasing the number of MPs from 577 to 500 (with 100 elected through PR), getting rid of jus soli as a path to French nationality, and restating our commitment to European integration in a Europe that official recognises its Judea-Christian roots and respects the sovereignty of nations.

2. Olivier Cadic, Alliance centriste, slogan: ‘La voix de la troisième France’ (the voice of the third France, an expression traditionally used with the meaning of ‘independents’, that is non-partisan voters, but Cadic considers the French ex-pat community to be the 3rd France). The Alliance centriste was created and is led by Jean Arthuis, a former Finance minister (during Chirac’s first presidency). Lives in Kent.

Already elected to the Assemblée des Français de l’Etranger, a consultative organ that is directly elected by French expats and elects their senators, Cadic opposes the introduction of income tax for expats (a major topic in the overseas campaign, mostly on the right side of the political spectrum). Unlike Dhiver, whose programme highlighted national issues, Cadic emphasises ex-pat issues: helping young French people who study abroad, encouraging the development of bilingual schools to allow French pupils to learn French (Cadic is involved in the Agency for the teaching of French abroad), simplifying administrative procedures for ex-pats, protecting the right to hold a double nationality, and ‘opening a cross-Channel metro [?] between Ashford and Calais’ to encourage trans-border work.

3. Anne-Marie Wolfsohn, independent. Her statement indicates that she has worked (as a lawyer) in the UK, Sweden and the Baltic countries (all of them in the third constituency), but it looks like she now lives in France.

Like Cadic, her first item is about her opposition to ex-pat income tax (in big letters on the first page), and the others address mostly ex-pat issues. Her proposals include facilitating R&D, creating a French business centre in London, encouraging the creation of more French schools abroad and in particular London (where most of the constituency’s voters reside), making administrative procedures easier for ex-pats, and creating a solidarity fund for French ex-pats living in countries affected by the crisis. The only national issue on her programme is deficit reduction.

4. Lucile Jamet, Front de Gauche. Slogan: ‘Le changement à gauche’ (Change on the left – nil point for effort). The Front de Gauche is the electoral coalition bringing together the Communist Party, Jean-Luc Mélenchon‘s Left Party and the extreme-left Unitarian Left (Gauche Unitaire, a break-away party from the Revolutionary Communist League LCR, which is now the NPA, New Anti-capitalist Party). No idea where she lives. The FdG doesn’t seem to place a lot of emphasis on the personality of their young (24 y.o.) candidate. I guess there’s only room for Mélenchon’s personality in the party.

Her proposals include measures to secure social services and pension rights for ex-pats, setting up an income tax for ex-pats (not clearly stated, but it is there if you read between the lines: ‘setting up a tax system that makes every citizen contribute to the extent of their means to their country by paying a tax differential’), and to increase the provision of French education abroad. Other measures relate to fighting tax evasion and tax heavens and promoting of North-South relations based on sustainable development. A picture of and statement by Jean-Luc Mélenchon appear at the bottom of page 2. The Front de Gauche argues that the presence of FdG MPs will secure the adoption of left-wing measures by François Hollande.

5. Gaspard Koenig, Parti Libéral Démocrate. Slogan: ‘Pour une France plus libre…’. Lives in London.

Koenig, who used to be a speechwriter for Christine Lagarde, has lived in London and worked for the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) for three years. His party is the heir to Alain Madelin’s now defunct Démocratie Libérale, the true voice of liberalism in France. Like Boutin’s PCD and Arthuis’ Alliance Centriste, this is one of the small parties that used to be part of the UDF (the Union for a French Democracy was a centre-right federation of parties that was created to support Giscard d’Estaing after he was elected president in 1974). It ceased to exist when the UMP was created to unify the right and centre-right. Its former member parties have either disappeared, merged into the UMP, turned into the MoDem or the Nouveau Centre (New Centre). It can be hard to keep track of all the components of the French centre-right.

He is opposed to the taxation of French ex-pats and wants to import into France the ‘best’ out of our constituency: a British model for universities (well done, us! we’re role models), Swedish-style reduction in public spending, Irish-style low taxes, and Danish flexicurity. He also wants to encourage the development of SMEs, break monopolies and increase competition (after all, he’s a liberal), put an end of public servants’ privileged status and to the ‘nanny state’, and raise the profile of immigration as an essential instrument to foster economic growth.

7. Olivier de Chazeaux Alliance Républicaine Ecologique et Sociales (ARES), Parti Radical and Nouveau Centre. Slogan: Un député d’expérience et d’action’ (an experienced and active MP). A lawyer, he is the former mayor of Levallois-Perret (city on the outskirts of Paris) and former MP (1997-2002) in the Hauts-de-Seine (a traditional right-wing stronghold, where Sarkozy was elected MP and mayor). There is no evidence to suggest he lives in the constituency.

Page 2 shows the candidate in the National Assembly (when he was a RPR MP), with former PM François Fillon, and with Jacques Chirac, shaking hands with Finnish former rally driver Ari Vatanen (who, if I’m not mistaken, ran as a RPR or UMP candidate in French EP elections). He is now affiliated with ARES, a confederation of yet more former UDF parties, including the Hervé Morin‘s Nouveau Centre (part of the UDF that joined forces with the UMP in previous elections; Morin was minister of Defence, 2007-10), and Jean-Louis Borloo‘s Radical Party, another former UDF party (Borloo was environment minister between 2007 and 2010).

His proposals include a ‘fair’ taxation for ex-pats, by which he means that if an ex-pat owns a home in France, it should not be taxed as a second home but as primary residency, for which taxation is lower; increasing financial help to French ex-pats who want to send their children to French secondary school and high schools abroad (they are often fee-paying and quite expensive); ensuring a fair recognition of the years worked abroad in the evaluation of pensions; facilitating administrative formalities when ex-pats return to France; and making sure that the budget deficit is reduced.

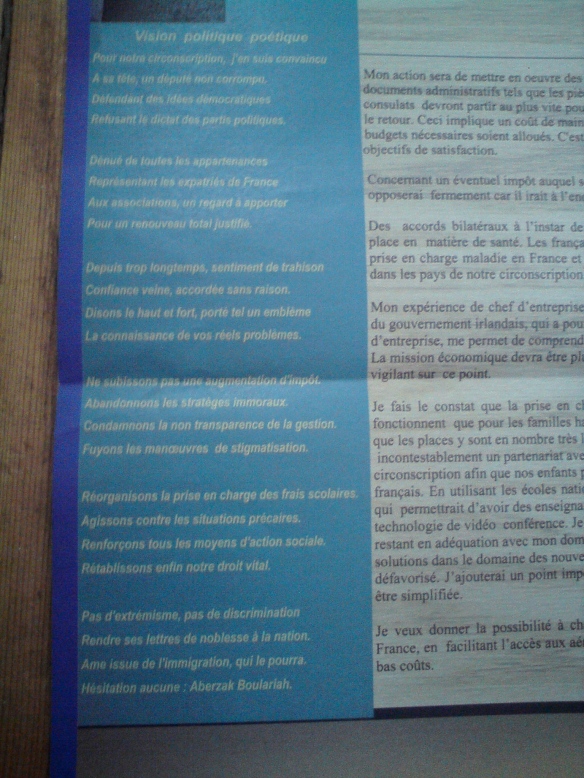

8. Aberzak Boulariah, independent. Slogan: ‘Ni à gauche, ni à droite. Droit au but’ (this one might be my favourite: neither left nor right, to the point). Lives in Ireland (well, that’s a nice change from England/London!)

In fact, he may be my favourite full stop, in particular because he makes rhymes (see bottom of the page above) and describes himself as a ‘surprising MP’ (you bet; his election would certainly constitute a surprise). He also claims to have a ‘poetic political vision’, that is, he expresses his political vision in verses:

Boulariah proposes to make administrative formalities faster for ex-pats (who cares about the other 60+ million French losers still living in France, right? This criticism can also be made against other candidates), develop bilateral agreements for health insurance, oppose the taxation of ex-pats, and increase the number of bursaries available to students unable to afford the fees for French schools.

9. Guy Le Guezennec, Front National (Rassemblement Bleu Marine). Slogan: ‘Pour une Assemblée vraiment nationale!’. Lives in Ashford.

For some reason, the FN candidate chose to illustrate his propaganda with a black and white picture (though being an old white man, a colour picture might have given a similar impression). The leaflet illustrates the new name chosen by the party for the parliamentary elections: Rassemblement Bleu Marine (bleu marine is a shade of blue in French, but it is obviously a rather cheesy word-play with Marine Le Pen’s first name).

Marine Le Pen features prominently on p.2 of the leaflet, with a picture and a statement from the leader herself. The lower half of p.2 includes pledges to oppose the austerity plan, stop immigration (I guess it’s only good for us French ex-pats), implement ‘national preference for health and social services, be tough on crime, introduce PR and popular referendums, defend ‘economic patriotism’, restore authority in schools, and stop communitarianism.

10. Axelle Lemaire, Socialist Party. Slogan: ‘Pour un nouveau départ, donnons une majorité au changement’ (a little too long to be catchy). Lives in London.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I have to say that I have met this candidate. Unless others have been poor at communicating with voters in Scotland, I believe that she is the only candidate who has come to our shores so far (the MoDem cabdidate comes tomorrow).

p.2 is illustrated with a picture of Lemaire with François Hollande. She promises to protect the right of bi-national citizens, refuses double taxation for ex-pats (in contradiction with PS policy?), and wants to make administrative formalities simpler, encourage student and professional mobility, secure pension rights acquired in other countries, and ‘democratise’ entry into French schools abroad. She says she has an international outlook (she was born and spent part of her youth in Quebec and has worked in the UK House of Commons), and her political priorities include cross-border issues, transport, sustainable energies, industrial co-operation, regulation of financial markets, gender equality and struggle against discrimination, and foreign relations.

These are the first 10 candidates. There are 10 more, but I have received electoral propaganda from only 7 of them.

To be continued…

![]()

Java : non installé ou la version détectée n’est pas compatible. Votre configuration ne satisfait pas les conditions requises pour pouvoir voter en toute sécurité par internet.

Java : non installé ou la version détectée n’est pas compatible. Votre configuration ne satisfait pas les conditions requises pour pouvoir voter en toute sécurité par internet.